The Other Talent War: Competing Through Alumni

Companies increasingly recognize the value of maintaining good relationships with former employees. Recent research, however, reveals a new insight: It’s also wise to pay attention to what your competitors’ former employees are up to.

Much has been said about the fact that companies are constantly fighting a war for talent. Given the importance of skilled human capital for competitive success, it is not surprising that companies dislike losing good people and expend considerable resources on attracting and retaining the best talent. However, if there’s one thing that businesses have learned in the ongoing talent war, it is that they don’t own their human capital — and many employees will eventually move on to new jobs.

Companies and managers must embrace this reality and reimagine how best to create and capture value with their former employees, whom many companies now refer to as “alumni.” Businesses increasingly have come to recognize the numerous advantages that their alumni can provide, and some companies, such as the management consulting firm McKinsey & Co., have well-organized alumni networks. In knowledge-based service businesses, in particular, it is common to look to former colleagues for referrals and even business, especially when those alumni work for a client of their former employer.

A company’s alumni can be valuable ambassadors for their previous employer and open up opportunities in other areas. For example, former employees can provide unique information about new pools of talent and about opportunities in geographic and product markets that managers might otherwise have missed. Former employees may themselves want to rejoin the company at a future date, becoming so-called “boomerang” employees. Although some companies distance themselves from former workers in order to discourage employees from leaving in the first place, others have developed and are expanding their alumni programs.

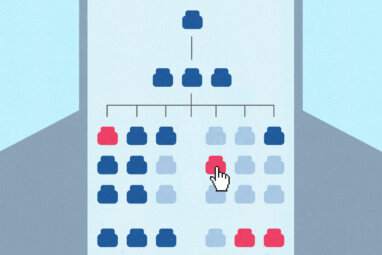

But even when companies are savvy about the value of their own alumni, rarely do they think about how their competitors’ alumni might affect their own business. To explore the dimensions of this hidden talent war, we studied outsourced work carried out by patent law firms for Fortune 500 clients in technology-driven industries over five years, focusing on how the law firms were impacted by their own and their competitors’ alumni when competing for business from clients. In our research, we uncovered systematic evidence that a competitor’s former employees can damage a firm’s client relationships.

Comment (1)

Archana Tyagi